“I wish I was normal.”

How many times have I heard people say this? How many times did I think it myself when I was younger? I don’t know, but hundreds, maybe thousands of times.

How about you? Have you ever thought, whispered, or screamed these words?

But what does it mean to be normal? Come with me on a small journey where we pull normality into the daylight and also spotlight things like:

- Where does the need to be normal come from?

- Why does the boring average usually become the goal and normal?

- Why is it sometimes dangerous and outright wrong to be normal?

- What can you do if you’re not normal, and it’s not because of what you do but because of who you are?

And what if we find that it’s not only your right but sometimes your responsibility not to be normal?

Let’s go.

What does it mean to be normal?

If you are norm-al, you comply with the norms.

According to the Cambridge Dictionary, a norm is:

- an accepted standard or a way of behaving or doing things that most people agree with,

- a situation or type of behaviour that is expected and considered to be typical.

And, for the word normal itself, the dictionary defines it as:

- ordinary or usual, the same as would be expected.

So, if you are normal, you act in a way that most people consider expected, typical, and accepted.

But something needs to be added here. The sentence above should end with “in a certain situation, in a specific group of people”.

And there’s something not quite right. If you feel you’re not normal, it’s often about who you are, not how you act. I’ll return to this.

Let’s first have a look at your career as an actor.

The parts you play

You learn from an early age to play different roles among different groups of people. Outwardly, you aren’t exactly the same person in every setting: in your family when you grew up, in your class at school, in your workplace, in your marriage, or on the football team.

Of course, you aren’t the same person because you adapt to the circumstances and have different positions and purposes in different groups.

Precisely, the Cambridge dictionary defines a role as:

- the position or purpose that someone or something has in a situation, organisation, society, or relationship.

As you can expect, each role you juggle in your life comes with its own set of expectations and standards, its own definition of what’s normal.

This is where you can get into trouble

There is always a potential for role conflict. For example, you may want to look after your young child while handling a challenging job. What’s expected from a normal mother among your friends or family might be hard to combine with what’s required from a normal manager in your company.

And what’s worse, you will sometimes end up in roles you feel are wrong for you, where there’s a conflict between what’s normal and your core values and who you really are.

This is a serious situation if you can’t get out of it, and it is probably one of the most common reasons why people suffer from mental health problems like depression and anxiety.

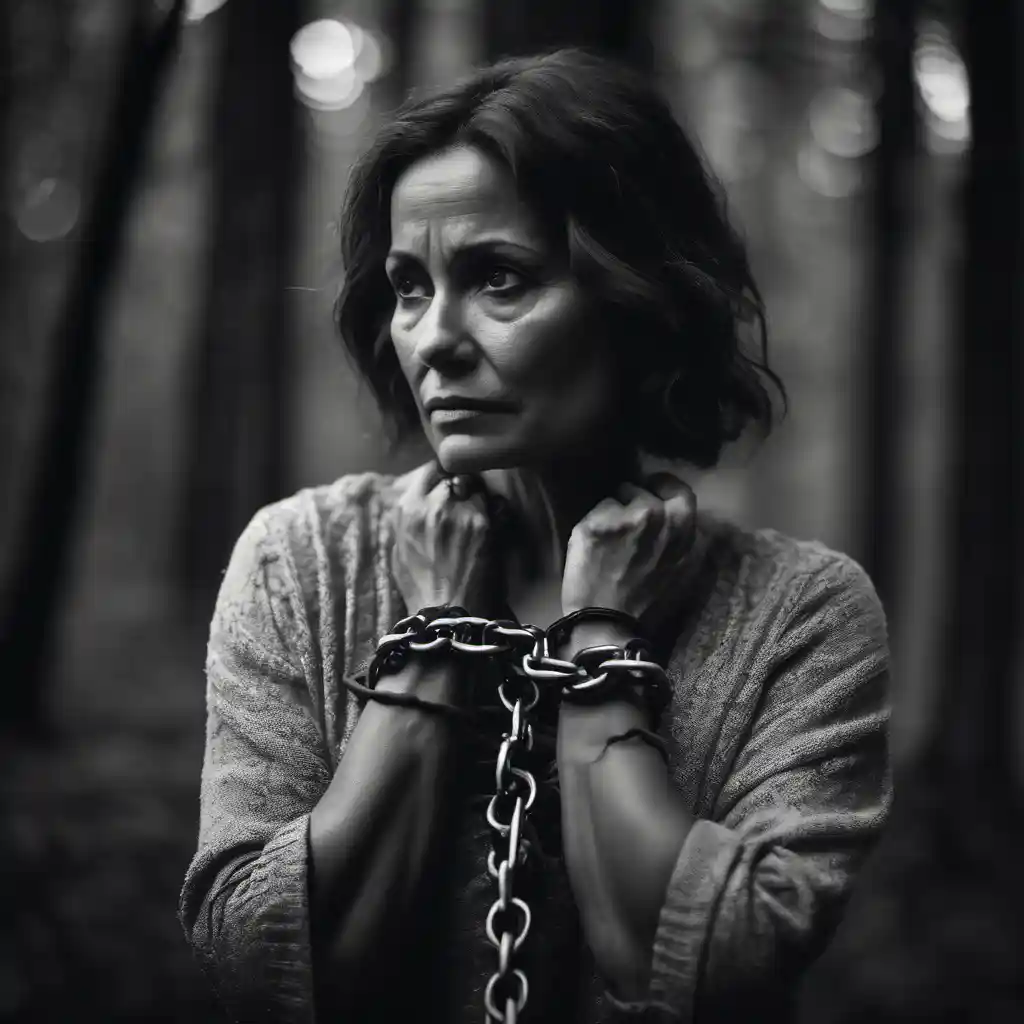

In the grip of normality

Where I grew up in rural Norway in the 1970s, normal boys and young men should be interested in fishing and hunting, cars and motorbikes, and football. Unfortunately, I preferred reading and writing, which I was rather discreet about.

Deviation from normality was quickly met with ridicule, bullying, and sometimes violence. I got my part of it all, even though I was pretty normal in most other ways. As a white, heterosexual male, I can probably not imagine how it must have been for gay persons, the few people of colour who lived in the area, and other “divergents”.

Norms are a double-edged sword. On one hand, by observing the norms in a group, you can learn to exist in the group without too much friction and conflict. On the other hand, norms can quickly become a vice that holds you “in your place” as a group member. And sadly, groups often tend to turn the vice screw as time goes by, and the gap you have fit into gets ever narrower.

Why is that?

From guidelines to shackles

All groups quickly start to create norms for behaviour to ensure their survival (or accomplishment of their goals).

Looking back a few hundred years, the community I grew up in was probably very homogenous. Almost everyone made their living from fishing and small farms. No one got strange ideas into their heads by reading because most people were illiterate. No one was openly gay because homosexuality was a capital crime. Everyone was a Christian, many in name only, because there were no alternatives, and they were all ethnically white. The probability of an early death was high. The main objective was to survive.

I imagine they had norms saying they should all pull their weight, help each other whenever necessary, share food in times of scarcity, and keep a positive attitude. Suppose someone thought, said, or even did something a little out of the ordinary. In that case, they might have been “punished” with laughter and good-natured teasing but not with a punched nose – provided they did their work well.

So, why was the “window of normality” so tight and narrow in the 1970s?

Closing the ranks

What does a group of people do when threatened? They close their ranks to protect themselves and survive.

Unfortunately, this doesn’t only happen when there’s a physical threat, like aggressive neighbours, a storm at sea, or failed crops. The group will also respond similarly when its uniformity and identity are threatened.

In the 1970s, some people went to university, some were politically radical, some (women) fought for gender equality, some ended their then-automatic membership in the Church of Norway, some listened to jazz or prog rock, some liked free-form poems or abstract paintings, some were immigrants from frighteningly alien cultures, and some even had skin colours other than white and pink!

At least we had heard a lot about people like that.

And we were supposed to constantly talk negatively about them, using words I definitely won’t repeat.

Under the threat of external influences and diversity, the community protected its identity by shrinking normality to a tiny, square box and zealously punished people who strayed outside it.

Turning harshness inwards

Whoever and wherever you are right now, you don’t live in rural Norway in the 1970s. If you have read this far, however, there’s a good chance you still struggle with “fitting in” and being “normal”.

Why? Aren’t things different now? Haven’t everyone got used to a lot more diversity? Shouldn’t it be much easier to fit in?

Of course not. While societies and cultures have changed dramatically in large areas of the world, the mechanics of the human brain and the dynamics of human groups haven’t changed at all.

At least in the Western world, communities, families, and other groups don’t have to fight starvation, storms at sea, or raiders from the neighbouring villages. However, with the constant influx of information and new ideas from all our television channels, the internet, and social media, group uniformity and identity are under more pressure than ever.

This means many groups will direct even more energy into enforcing conformity. The group’s objective isn’t physical survival in a harsh world but the survival of the group as such and its identity. Sadly, this often means the harshness is moved from the outside world to the group interior.

Group pressure and rigid norms can churn you to pieces if you allow it. The fundamental first step to avoid this is to pull them into the daylight, examine them, and understand them.

The boring average

When a group’s main objective is physical survival, its norms will be best practices based on experience. “This is what we know will work.”

These norms have the same strengths and weaknesses as traditions. They can be helpful guidelines as long as the circumstances don’t change. If the circumstances do change, the norms can be oppressive or even dangerous for the individuals.

When a group’s primary focus turns to preserving its identity and uniformity, it must shape norms that are readily acceptable to the majority of its members. This is like finding the lowest common denominator when adding fractions in math. The average is the norm and the goal.

The point is that a group’s norms aren’t necessarily the truth, beneficial for the group’s members, or even ethically defendable. They are the boring average the group settled on without conscious thinking or open discussion.

The danger of normality

Anyone who feels obliged to always follow the norms of their groups should read up on groupthink. If you set aside your needs, beliefs, and knowledge and mindlessly accept what “everyone else” is thinking, you can contribute to bad or even disastrous decisions.

I dare to claim that the human species would have been extinct long before it left the Great Rift Valley if everyone was normal.

“Why do you cover yourself with the skins of dead animals?” “Well, it’s really cold here. I don’t want to freeze to death.” “No one in our clan has ever done such a stupid thing. Idiot! You stink!”

Very few people in a given group are average. The average is just an imagined line dividing the individuals who are evenly spread out to the left and right of that line. However, group pressure through norms can make people believe or pretend they are average.

What a waste.

The right to deviate

Leonardo da Vinci and Albert Einstein weren’t normal. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Freddie Mercury weren’t normal. Martin Luther King and Nelson Mandela weren’t normal.

How many geniuses and inspiring leaders have we lost through beating children to submission, ridiculing teenagers, burning dissenters at the stake, or ostracising someone for the grave crime of independent thinking?

And we who are neither geniuses nor great leaders still have the right to be ourselves, keep our beliefs and dreams, and be the unique individuals we are.

All humans are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

– Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

This is your right. No one has a right to force you into something else.

The difficult choices

But it’s more complicated than this.

You are most likely members of groups where you can’t just stand up for yourself and cite the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Oh, how fast would the jaws of group pressure grab you by the throat if you do?

Imagine coming out as gay in a homophobic family, for instance.

And even worse, what if you can’t leave the group? You can’t choose your family. And what if you are a woman and your dream job is to be a finance manager, and the only company in your area where you get a job like that has an oppressive, sexist culture?

In most cases, you have options, although they all might be difficult.

You can choose to:

- Make a stand and try to change the culture and norms of the group.

- Leave the group or at least disengage from it.

- Stay put and risk continuous suffering.

The art of accounting

We often stay in uncomfortable or even harmful situations because long-term moderate suffering seems more manageable than the relatively short, sharp pain of change.

However, it’s your life, and for all we know, it might be the only one you’ll get. Imagine the bottom line of your life’s accounting report when it one day ends. It might be worth investing in some pain of change now instead of letting constant suffering wear you slowly down until there’s nothing left.

You can’t choose your family, but you can decide to be less involved in it. You can relocate to find your dream job in a more welcoming company. You can also discover that you dreamed of that job because of the salary and prestige and decide that quality of life is more important.

All of these choices might result in retaliation from your groups, such as your family, colleagues, and friends. Remember, however, the bottom line.

To pick a fight

Of course, you can try to change the norms in your groups. If you succeed, it might be the most rewarding thing you’ve ever done. If you fail, it may, in some cases, be devastating.

It’s wise to choose your battles. The best generals only attack if victory is probable. You must know what you’re up against before you charge in. Changing a group’s culture and norms is usually challenging and sometimes impossible if you can’t afford the luxury of endless patience.

The best generals also know that withdrawal isn’t the same as defeat. Sometimes, withdrawing from one environment is necessary to achieve a more significant objective: a final victory – or a happy life.

If the cost of making changes is too high, you should leave or create some distance from a group. That’s the rational and responsible thing to do.

When your actions aren’t the problem

Now, let’s return to the fact that normality isn’t always about our actions. If one of my remote ancestors caught a lot of herring and didn’t share it with his neighbour, whose fishing nets turned out to be empty, he probably failed to act according to the community group’s norms.

Sadly, you might feel you’re not normal for other reasons. It’s not what you do (or not) that makes you fail in the eyes of the group. It’s who you are. You might be gay in a homophobic environment, a girl in a society that prefers boys, or a thinking and writing young man in a time and place where moose-hunting is considered the standard.

It’s not acceptable to be punished for who you are. You can choose your actions, but you can’t choose your core personality. Provided your personality doesn’t make you harm other living beings intentionally, it’s not wrong to be you.

What’s wrong is the norms and group pressure demanding you must change or at least fake it.

What you feel is not who you are

“I wish I was normal.”

How many times have I heard people say these words, but not because of what they do, not even because of who they really are, but because they have mental health challenges like depression or anxiety?

If this is you, wishing to be normal might just mean you don’t want to feel sad or anxious.

However, the still existing stigma of having mental challenges makes it feel like it’s about who you are. And the expectations of a specific behaviour in a particular situation (“everyone has to be happy at a family party”) make it about how you act.

Remember this: what you feel is not who you are. Depression or anxiety is something you suffer from; it’s not you. No more than physical conditions like a broken arm or a toothache are you.

Judging or punishing you for something you suffer from isn’t only irrational; it’s also cruel. And, of course, you have the right to take any measure necessary to protect yourself and focus on getting better, even if what you do isn’t “normal.”

Your right and responsibility

It’s human nature to want to “fit in” in every social group we come across, the family, your team in the workplace, organisations we volunteer for, or sports teams.

However, as we’ve seen, being norm-al means following each group’s norms, which might not be healthy or ethically defendable in some cases.

It’s your right and your responsibility as a thinking and feeling human being to decide if the norms are right or wrong.

Peer pressure will undoubtedly make this difficult for you in some environments. Still, you aren’t born with an obligation to be something you aren’t. You shouldn’t suffer eternally because of unspoken, undebated, and unreflected rules.

It might seem easiest to do nothing, but doing so is burying your head in the sand and betraying your present and future self.

Whether you fight for change or distance yourself from the group, it’s almost always brave and difficult.

Be a hero!

+ There are no comments

Add yours