As a Norwegian living in England, I enjoy exploring the similarities and differences between English and Norwegian culture. One similarity stands out: the English and the Norwegians greatly value privacy.

I will show you how this apparent similarity has quite different geographical and historical roots in the two countries and that privacy, although vigorously defended, has a somewhat different meaning in England and Norway.

Don’t intrude on us (please)!

Picture yourself boarding a bus. As it turns out, there’s only one other passenger. She looks friendly enough. Fancy a chat? Why not sit down next to her and strike up a conversation?

No, you won’t. Not if you’re English or Norwegian. The poor woman would think you’re drunk, or dangerous, or presumably both.

Of course, you walk past her to sit down at a safe distance. If a brief moment of eye contact happens, you might say “Morning” (if you’re English) or smile and nod (if you’re Norwegian and in a perfect mood).

We don’t want to intrude or disturb, and people we come across will expect us not to.

The Right to be left alone

People from more outgoing cultures often say the English are pretty reserved. The Norwegians are even worse, sometimes described as cold and dismissive by foreigners after the first encounter.

I don’t think there’s much of a difference. The English might seem slightly more accessible because of their frequent use of words like “please” and “sorry”, even though such phrases of politeness might not be much heartfelt. Norwegians won’t say “sorry” unless they are sorry – or sarcastic.

So, what’s wrong with the English, the Norwegians, and people from comparable cultures?

Nothing at all. We just cherish our personal spaces, both the physical and mental ones, and our time. We want to have some degree of control over what we share, when, and with whom. We don’t like to be randomly invaded.

We exercise our right to be left alone if and when that’s what we want.

Cultural introversion?

Any introverted person from any culture would pay good money to be allowed to exercise this right. Introverts are often wrongly believed to be asocial and unfriendly when all they want is – exactly – to control how, when, and with whom they socialise.

I think it’s defendable, then, to say that the English and Norwegians display some introverted traits on a cultural level, regardless of their individual personalities.

How did this come about?

Spatial privacy

Norwegians – loners by nature?

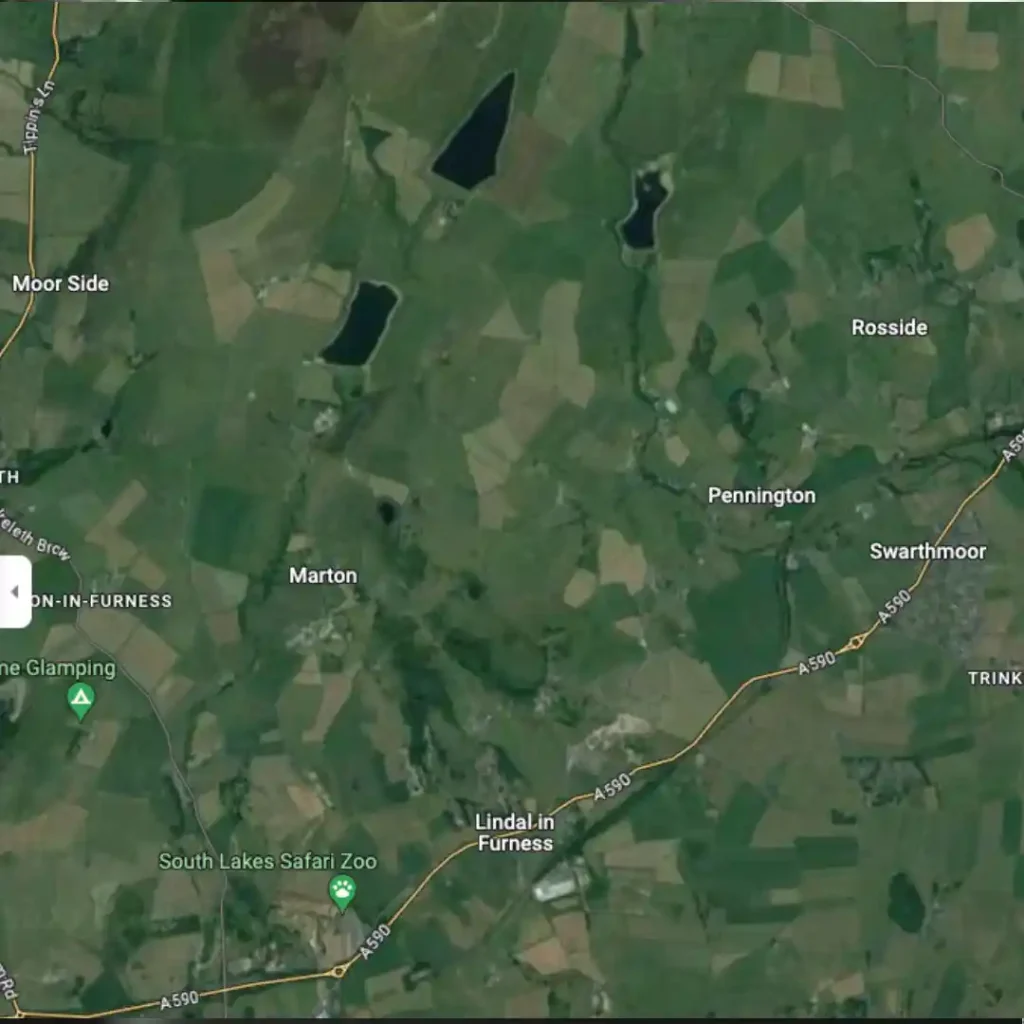

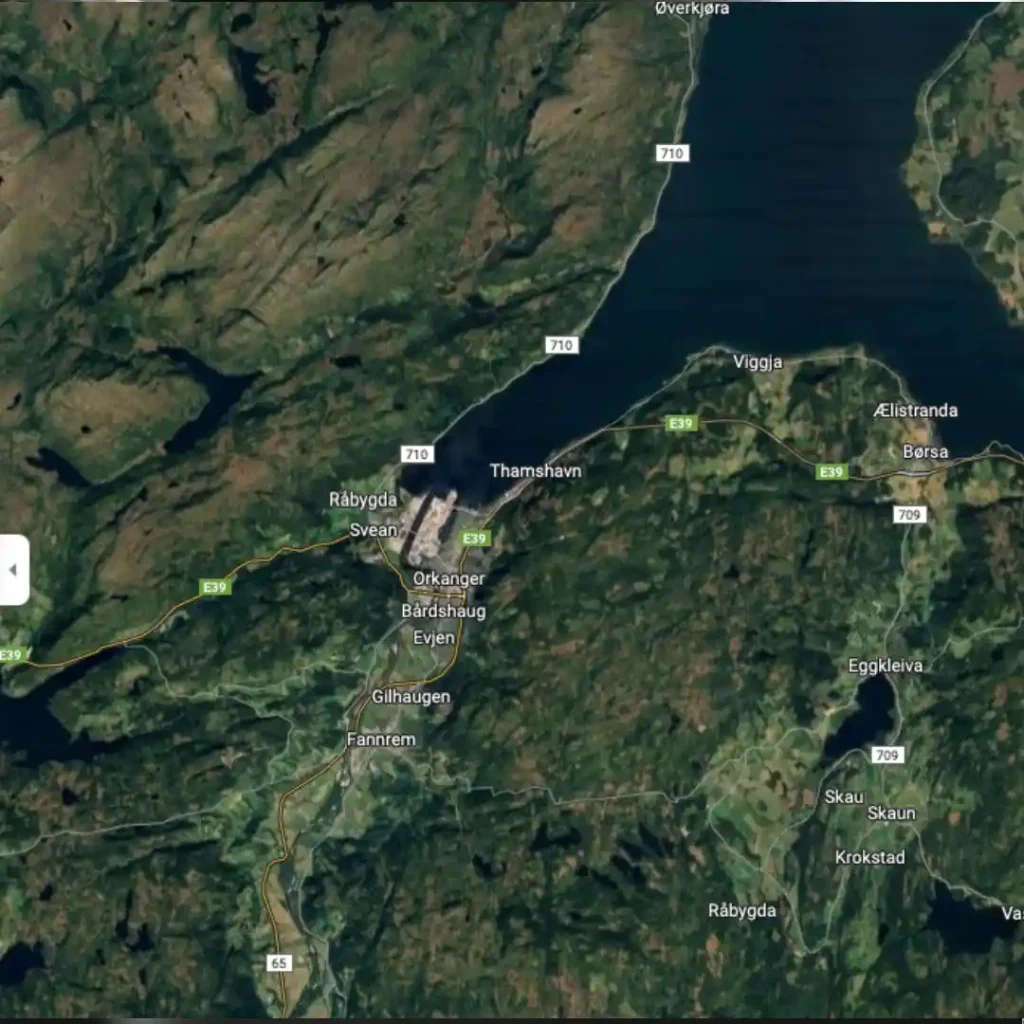

It’s easier to find tangible reasons among the Norwegians than among the English. Look out the window the next time you’re on a plane over England or Norway.

Over rural England, you will mostly see green fields. Period. Green fields with scattered villages and towns.

Over rural Norway, you will see mountains and forests, ripped up here and there by deep fjords and lakes.

Oh yes, down there, in between all the stone and wood and water, you’ll see patches of inhabited land along the coast and in the river valleys.

But that’s not all.

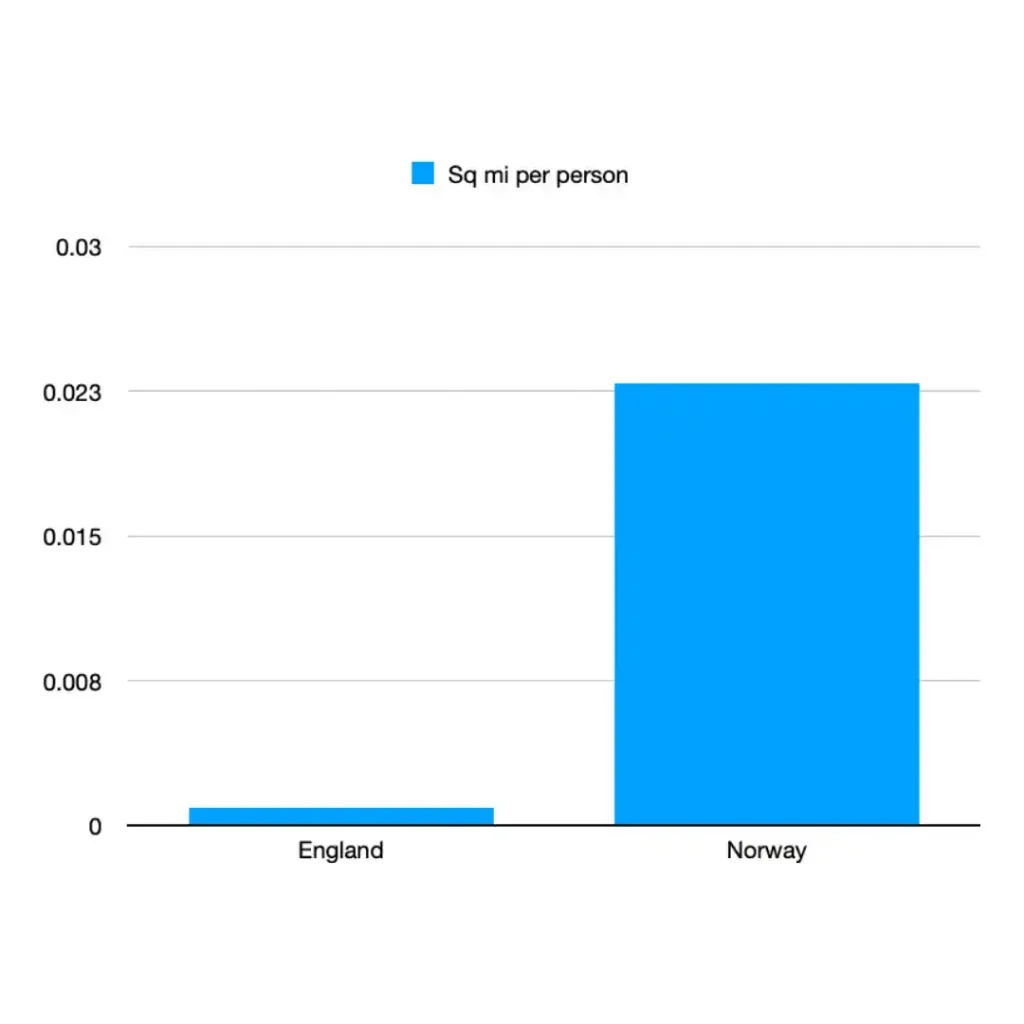

In 2022, 57.11 million people lived in the 51,320 square miles of England, while the 5.46 million Norwegians could spread out on 125,180 square miles of primarily rocky ground if they wanted to.

In other words, each Norwegian could have 0.02 square miles to himself, while an Englishman would have to do with less than 0.001 square miles. Or, ten football fields for the Norwegian and half a field for the Englishman.

If you want to exercise the right to be left alone in a physical sense, Norway is the place to be.

The English – villagers by choice?

England would have felt more spacious a thousand years ago. The population at the time of the Norman conquest is estimated to have been between 2 and 3.5 million (while there were less than 200,000 Norwegians).

Still, it seems the English sought each other’s company more than the Norwegians did. Living in villages is and was commonplace in England.

English village, image by Albrecht Fietz from Pixabay.

Norwegian coastal countryside, image by Dieter from Pixabay.

Most rural Norwegians lived on farmsteads, often without any neighbours in sight.

I don’t think this difference was a matter of choice. Before the Industrial Revolution, land ownership was the primary source of wealth. The English landscape makes it possible to gain control over large areas of productive land if you are powerful enough. English rulers would give their knights and noblemen land and, subsequently, inheritable wealth in exchange for loyalty.

The wealthy landowners still needed a considerable workforce, though. And if ordinary people didn’t own the land they worked on, living in villages was probably the logical and practical thing to do. They could even help defend each other in dire times.

Norway didn’t have much aristocracy. Few areas had the geography and topology to allow large-scale, efficient agriculture, and individuals rarely owned fertile land enough to become extremely rich. We didn’t have many lords of the manor, and hardly any manors comparable to the English ones.

Of course, Norway had people who didn’t own the land they worked on. One of my grandfathers was a crofter even midway into the twentieth century. Still, people generally lived on the land they got their livelihood from.

Industrial upheaval

England was the cradle of the industrial revolution and launched a vast migration from the country to the industrial towns and cities. Some sources suggest that the urban population outgrew the rural population around 1850.

Many of the former village people of England initially lived in cramped, hideous slums and later in the well-known endless rows of narrow terraced houses.

Norwegians, often slow to adapt to new trends, needed time to catch up with industrialisation and urbanisation. The urban population finally became bigger than the rural population sometime well into the twentieth century.

Large-scale development of housing areas for work migrants didn’t happen until after WW2, resulting in typical 1950s – 1970s suburbs.

Quite a few Norwegians now live in terraced houses, but this is a temporary step on the property ladder for many people. Deep down, Norwegians still want their own farm. Even if all of the farm work is done with a lawn mower and the estate only reaches a few feet from the house’s walls, it’s essential to own some land on all sides of the house!

Don’t come too close!

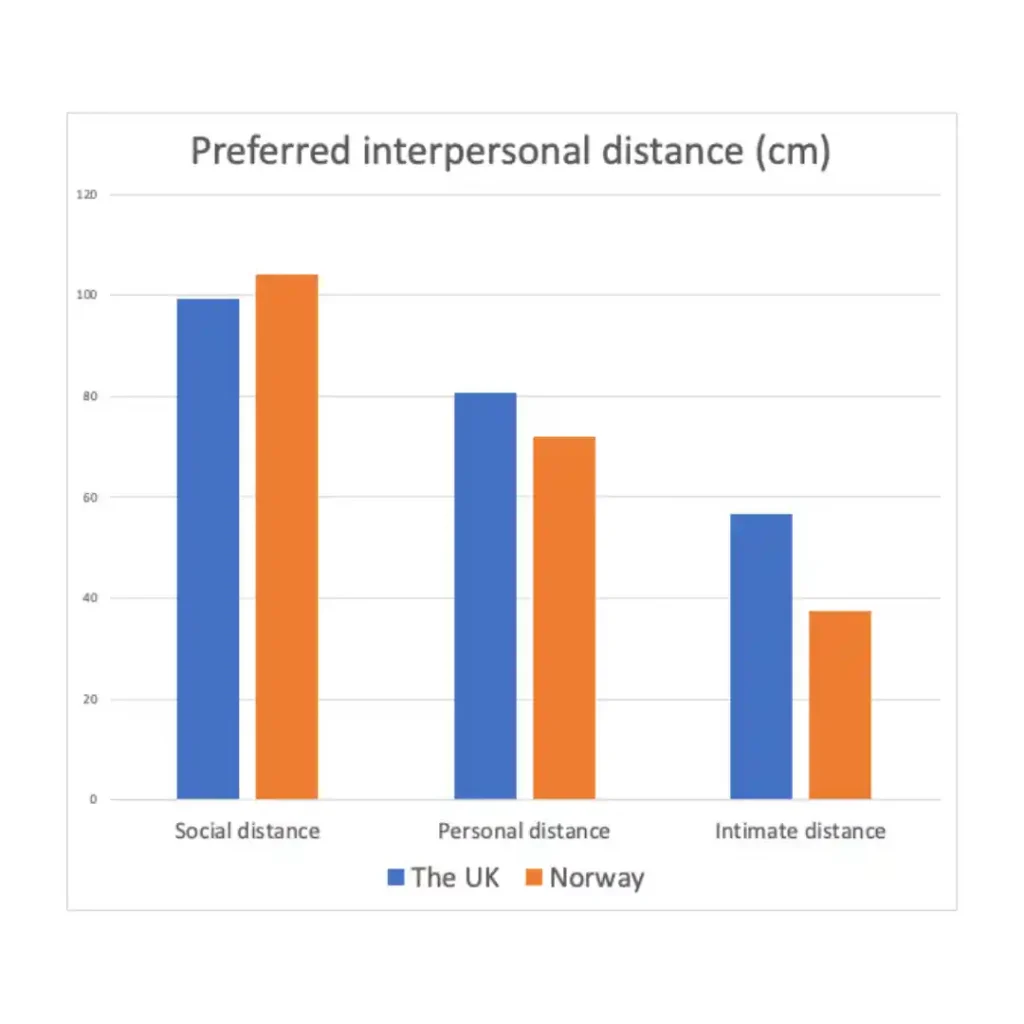

The space we desire around our houses is one thing, but how about interpersonal space? What distance do we need between ourselves and another person without feeling discomfort? This is quite interesting as a physical indicator of our privacy preferences.

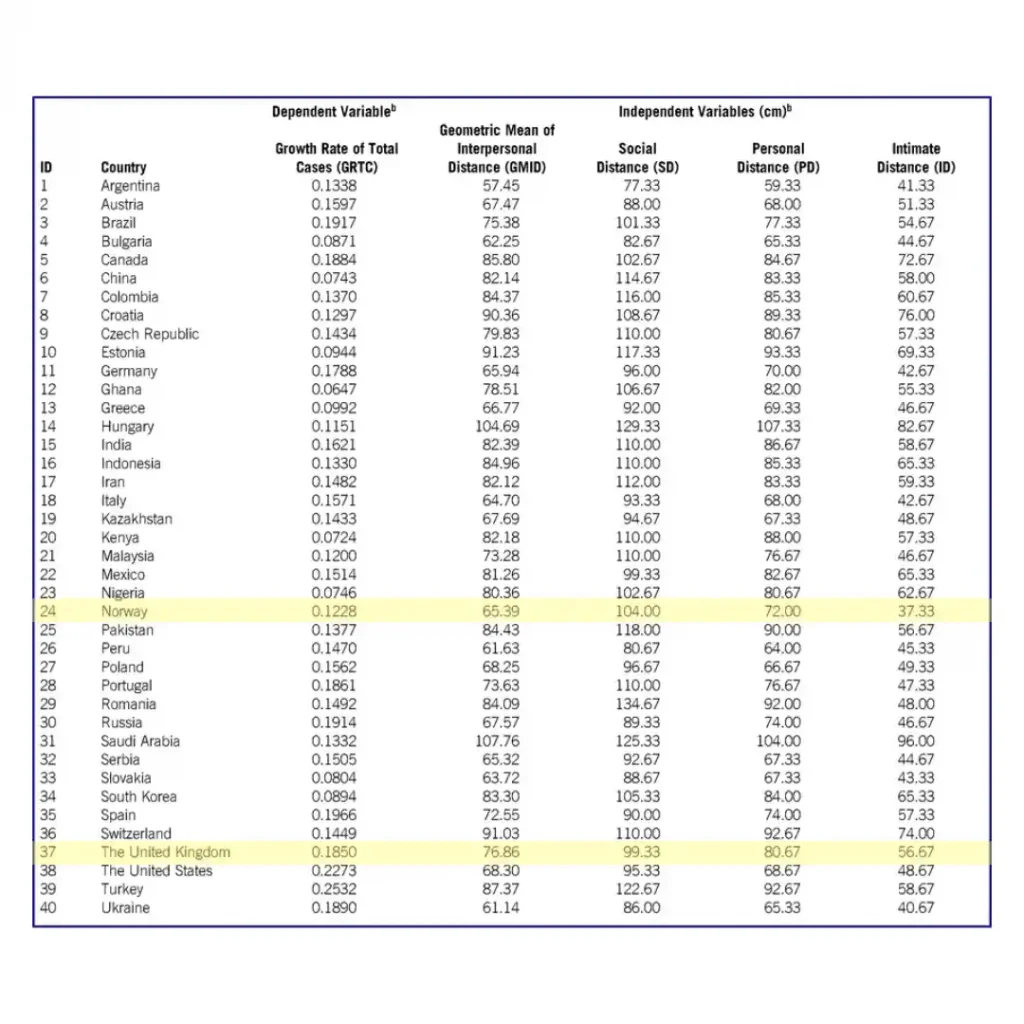

Research looking at our preferred interpersonal space in different situations shows that the English and Norwegians are similar regarding social distance. This is the preferred distance to a stranger, for instance, in a business setting. Both the English and the Norwegians need to keep this stranger at arm’s length (99 cm for the English and 104 cm for the Norwegians, to be specific).

However, the English and the Norwegians arrived at this similarity along two different paths if we look at it through the geographical and historical lenses we used above.

I believe Norwegians have developed a cultural affinity for privacy through centuries of living in relative isolation, with abundant space around themselves and their families. Remember, the majority of Norwegians left their farmsteads only two or three generations ago.

The English were crammed into villages, towns, and cities much earlier. Could an English obsession with privacy have developed because of a geographical and historical deprivation of personal space?

It’s plausible. But we must dig into subtler differences between the English and the Norwegians.

Information privacy

Let’s return to the bus and imagine you’re stuck in a traffic jam for an hour. Then, perhaps, you will talk to the only other passenger. How will you start?

Whether you are English or Norwegian, you will talk about the weather. Because of its neutrality, it’s the favourite icebreaker topic in both cultures. But how you would proceed is more interesting.

After some communal moaning about the traffic situation, you may ask each other where you’re travelling today. But would you ask questions about where she comes from, what she’s doing for a living, her education, or her view on a political issue?

You might, if you’re Norwegian and the traffic jam lasts long enough.

You won’t if you’re English. Your fellow passenger would think you’re extremely rude.

Reading the anthropologist Kate Fox’s book Watching the English has given me valuable information about my new homeland’s culture – and quite a few good laughs. This is what Fox says about revealing private information:

‘Private’ information is not given away lightly or cheaply to all and sundry, but only to those we know and trust. This is one of the reasons why foreigners often complain that the English are cold, reserved, unfriendly and standoffish. In most other cultures, revealing basic personal data – your name, what you do for a living, whether you are married or have children, where you live – is no big deal: in England, extracting such apparently trivial information from a new acquaintance can be like pulling teeth; every question makes us wince and recoil.

Fox, Kate. Watching the English: The International Bestseller Revised and Updated (p. 44). Hodder & Stoughton. Kindle Edition.

A matter of trust

How can it be that the Norwegians relatively quickly talk to strangers about subjects the English find tremendously private? Apparently, the English and Norwegian borders between private and public information don’t coincide. Why?

The keyword is trust. Who do you trust enough to reveal specific information about yourself without fear of the information being used to your disadvantage? The English might think the Norwegians are somewhat naive, but that’s not true.

There might be general differences in trust levels.

Trust in public institutions

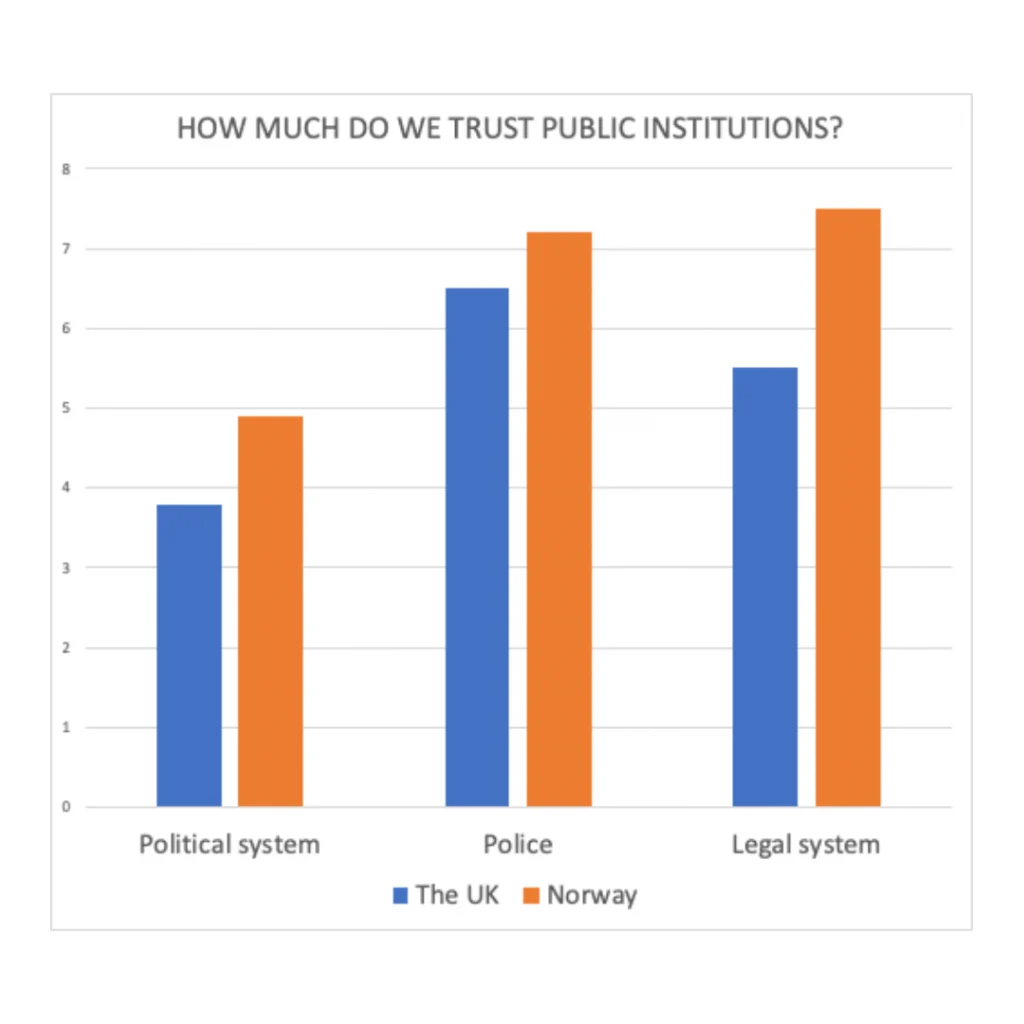

Where 0 = “no trust at all” and 10 = “complete trust”.

A 2015 OECD report showed apparent differences in how much the Europeans trusted the political system, the police, and the legal system. For the UK and Norway, the differences are illustrated in the chart.

When asked about the government, 64 % of the Norwegians said they trusted their government, compared to 48 % of the Brits.

Norway, like the other Nordic countries, is a relatively regulated society. This means a certain level of transparency and legal control over what private persons and public institutions can and cannot do. Most media houses still take journalism seriously and do a comparably good job as indispensable watchdogs in a working democracy.

Reasons for a lower level of trust in public institutions in the UK might be less transparency and the fact that newspaper articles that focus on more essential things than the sensational adulterous sex life of reality show participants are hard to find.

By the way, when asked if they trusted journalists, 85 % of the Norwegians and 59 % of the Brits said they did.

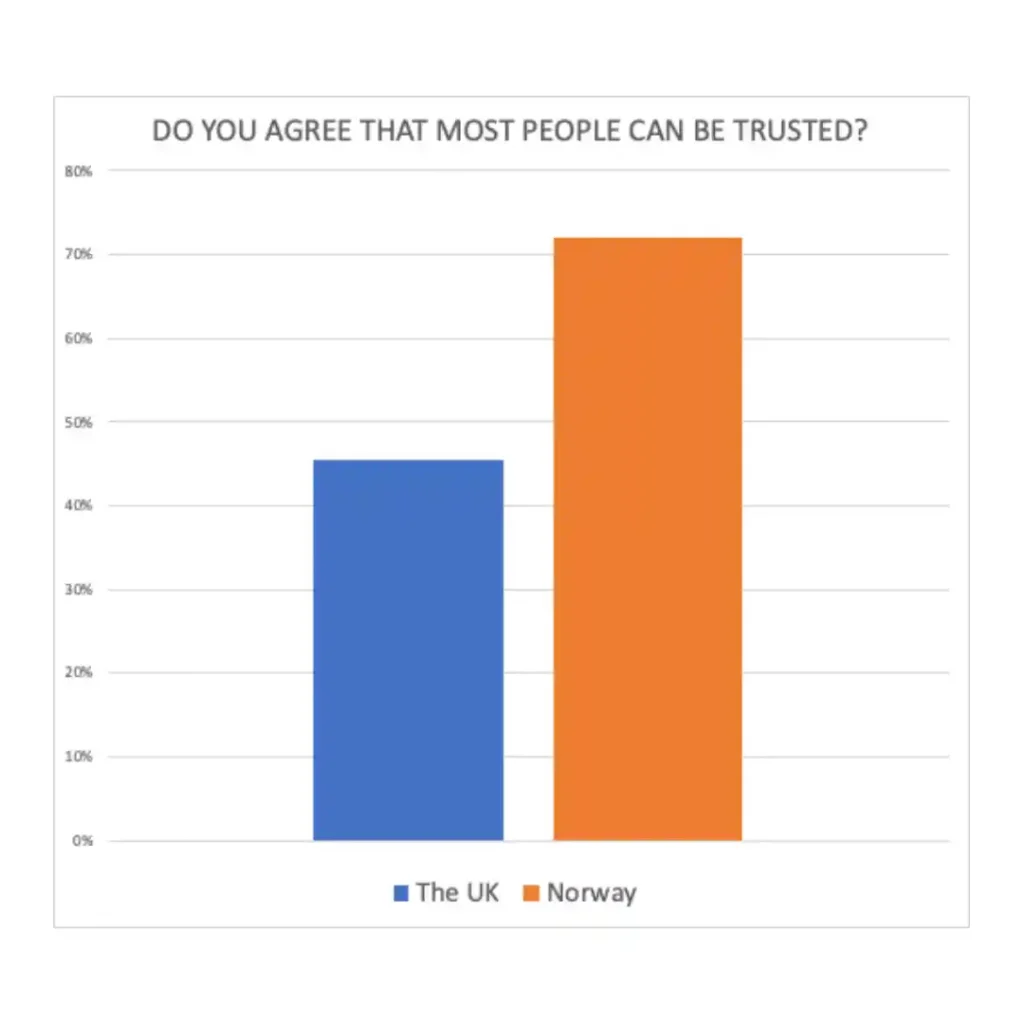

Trust in other people

The same OECD report also showed a difference in general trust in others. While 72 % of the Norwegians agreed that most people can be trusted, only 45 % of the Brits did.

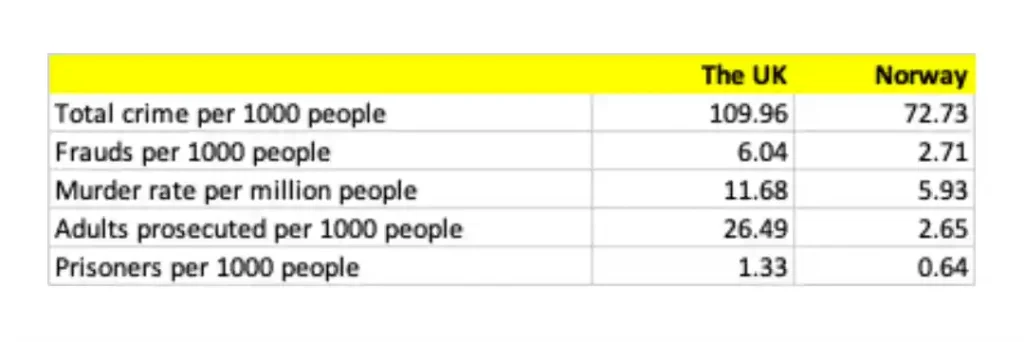

According to crime statistics from Nation Master, some figures (but not all) indicate that the Brits might have good reasons to be slightly more suspicious towards strangers.

Who do we let in?

As we have seen, what’s considered private information is somewhat different in England and Norway. Still, while a Norwegian might discuss his occupation, and even his salary, with someone on the bus, this doesn’t mean the fellow traveller is inside the Norwegian’s guarded perimeter.

So, who are the “in-groups” of the English and Norwegians? Who do they trust and confide in with what they deem private?

Of course, this is highly individual, and comparable statistics are scarce. However, after living in England for one year so far, I will share my opinion. It seems to me that family is more important to the English and that family values are still more conservative than in Norway.

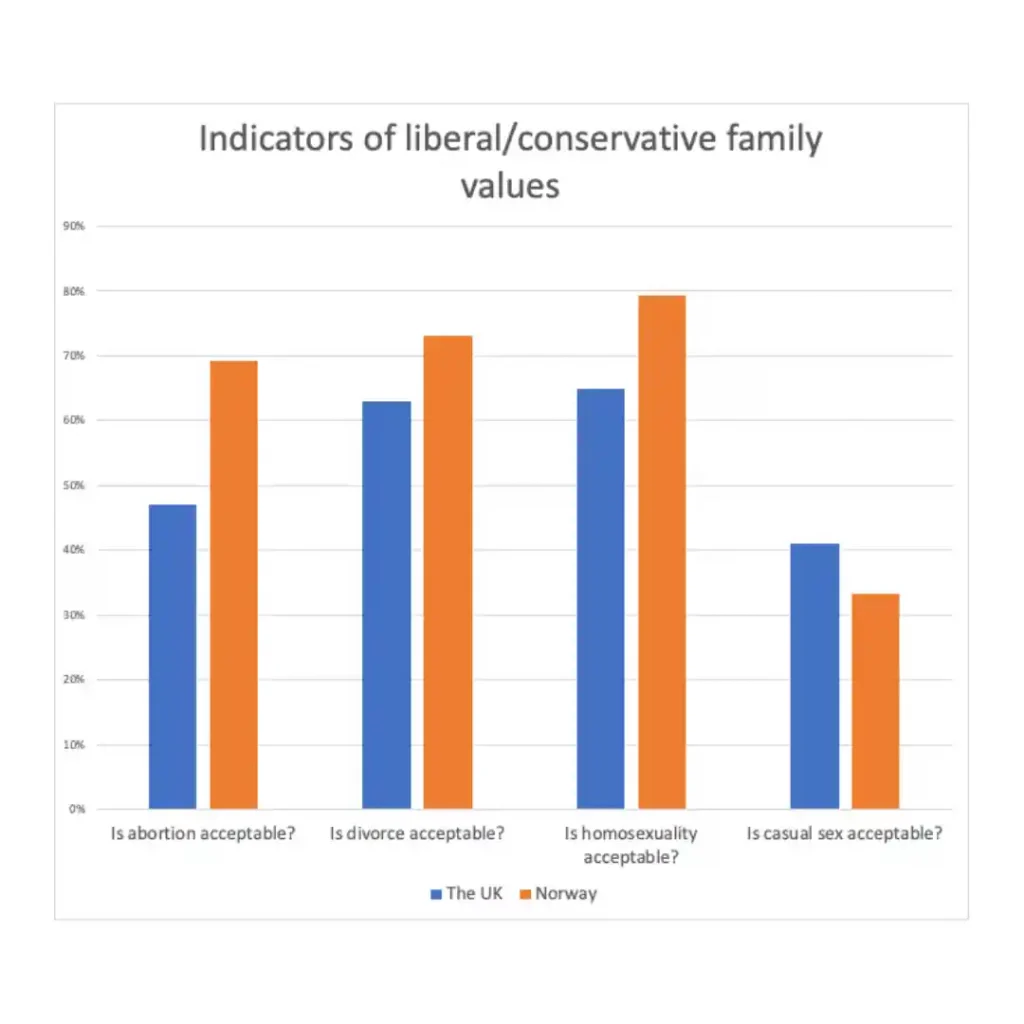

These examples from euronews.com illustrate some of the differences.

Oh yes, the British were more liberal than the Norwegians on one of the questions, but let’s leave it there.

I believe the English, to a greater degree, turn their privacy shield off in the presence of their family. The Norwegians, to whom the family outside the individual household is of lesser importance, will have to find their own in-group. It’s not enough to be a sister or an uncle. You have to prove you deserve membership.

It’s hard to get a Norwegian to let you in, but once you’re inside, you have a trusted friend for life. This is just a saying, but we can find some proof for it if we look back at the table showing preferred interpersonal space.

When the Norwegians meet strangers, they prefer to keep them a bit further away than the English (social distance). Once they get to know someone, the Norwegians already agree to keep them closer (personal distance).

And towards the closest persons, we see the Norwegians can be, well, quite intimate.

+ There are no comments

Add yours